How to Get All Custom Properties on a Page in JavaScript

When I have a question about how to do something with CSS, I often find the answer on CSS-Tricks. I’m guessing that’s true for a lot of you too. It’s been the go-to for CSS knowledge for as long as I can remember.

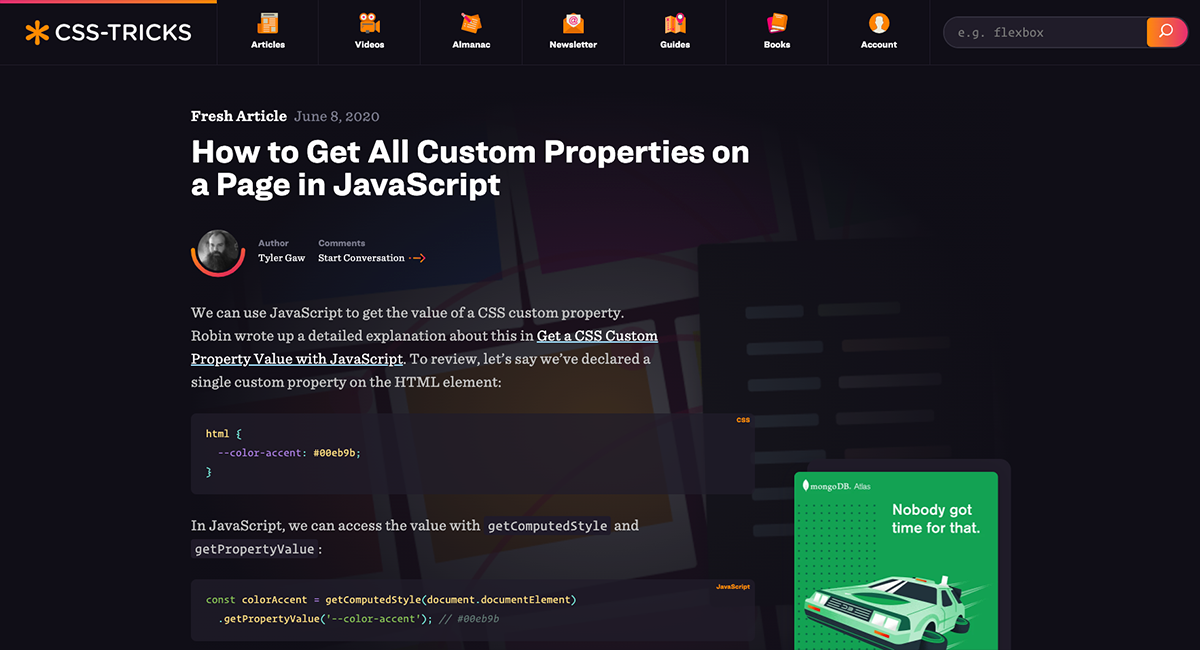

If one day you find yourself searching for help working with CSS custom properties in JavaScript, you might find yourself on an article on CSS-Tricks written by me. Because, last Monday, June 8th 2020 I have an article published on that invaluable website.

Update: In early 2022, CSS-Tricks was bought by DigitalOcean. Since then, they haven’t done much with it. At the time of this update, the last post was almost eight months ago. I don’t trust that they’ll be a good steward going forward. I’d saw we’ll start losing posts or the entire site will just go offline at some point in the not so distant future. I don’t want to lose the contents of my post, so I’m reposting it here, down below, where I know it will stay online.

The Process

I used the technique I describe in the article at work for a one-off project. It was fun code to work on. It required a lot of following a trail of different browser APIs. I latch on to work like that. After I had the code working for the project I abstracted it to stand-alone examples. I started writing a draft for my personal blog. But, I wrote too many words. I got bogged down. The draft was over 3,000 words, wasn't finished, and wasn’t very good. I couldn’t motivate myself to finish it. So, it sat. In a branch, unfinished. Not the first blog post I’d abandoned.

Months later, I was listening to an interview with Eva Holland on the Longform Podcast. In it, she talked about how during her career she’d cold pitched articles to editors at publications. This wasn’t the first time I’d heard this from writers, but something about hearing it that time stuck with me.

“I should do that!”, I thought. Specifically, I thought I should pitch the custom properties article I’d given up on to the best web development publication I could think of.

Was that a thing? Is that how articles on CSS-Tricks come to be? Turns out that’s one way. I’d always assumed the only way to get an article on a site like CSS-Tricks was to get an invitation to do so. That is not the case. They have a pitch form available to everyone. Chris even asks you to write a guest post on his site.

So, I pitched the article idea. It wasn’t perfect and the draft wasn’t done. Chris got back to me in a few days and said, “go for it.” It took me about a month to get back up to speed on the code and write a full draft. I’m a slow writer. Within a few days of submitting the draft, Geoff began the editing process. We did a few rounds of copy edits, small style updates, and checks to make sure we had consistent and accurate code samples and CodePen links. June 8th was the day that fit the publishing calendar. And now I’m super excited to have it live.

A post like this doesn’t get a million comments or make the front page of Hacker News. That’s not its purpose. A post like this exists for the long term. It’s a utility that will sit in wait until the day you need it. On that day, it’ll be waiting for you, ready to help.

Full article reposted from CSS-Tricks

Originally published June 8, 2020 at https://css-tricks.com/how-to-get-all-custom-properties-on-a-page-in-javascript/

We can use JavaScript to get the value of a CSS custom property. Robin wrote up a detailed explanation about this in Get a CSS Custom Property Value with JavaScript. To review, let’s say we’ve declared a single custom property on the HTML element:

html {

--color-accent: #00eb9b;

}In JavaScript, we can access the value with getComputedStyle and getPropertyValue:

const colorAccent = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement)

.getPropertyValue('--color-accent'); // #00eb9bPerfect. Now we have access to our accent color in JavaScript. You know what’s cool? If we change that color in CSS, it updates in JavaScript as well! Handy.

What happens, though, when it’s not just one property we need access to in JavaScript, but a whole bunch of them?

html {

--color-accent: #00eb9b;

--color-accent-secondary: #9db4ff;

--color-accent-tertiary: #f2c0ea;

--color-text: #292929;

--color-divider: #d7d7d7;

}We end up with JavaScript that looks like this:

const colorAccent = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement).getPropertyValue('--color-accent'); // #00eb9b

const colorAccentSecondary = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement).getPropertyValue('--color-accent-secondary'); // #9db4ff

const colorAccentTertiary = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement).getPropertyValue('--color-accent-tertiary'); // #f2c0ea

const colorText = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement).getPropertyValue('--color-text'); // #292929

const colorDivider = getComputedStyle(document.documentElement).getPropertyValue('--color-text'); // #d7d7d7We’re repeating ourselves a lot. We could shorten each one of these lines by abstracting the common tasks to a function.

const getCSSProp = (element, propName) => getComputedStyle(element).getPropertyValue(propName);

const colorAccent = getCSSProp(document.documentElement, '--color-accent'); // #00eb9b

// repeat for each custom property...That helps reduce code repetition, but we still have a less-than-ideal situation. Every time we add a custom property in CSS, we have to write another line of JavaScript to access it. This can and does work fine if we only have a few custom properties. I’ve used this setup on production projects before. But, it’s also possible to automate this.

Let’s walk through the process of automating it by making a working thing.

What are we making?

We’ll make a color palette, which is a common feature in pattern libraries. We’ll generate a grid of color swatches from our CSS custom properties.

Here’s the complete demo that we’ll build step-by-step.

Let’s set the stage. We’ll use an unordered list to display our palette. Each swatch is a <li> element that we’ll render with JavaScript.

<ul class="colors"></ul>The CSS for the grid layout isn’t pertinent to the technique in this post, so we won’t look at in detail. It’s available in the CodePen demo.

Now that we have our HTML and CSS in place, we’ll focus on the JavaScript. Here’s an outline of what we’ll do with our code:

- Get all stylesheets on a page, both external and internal

- Discard any stylesheets hosted on third-party domains

- Get all rules for the remaining stylesheets

- Discard any rules that aren’t basic style rules

- Get the name and value of all CSS properties

- Discard non-custom CSS properties

- Build HTML to display the color swatches

Let’s get to it.

Step 1: Get all stylesheets on a page

The first thing we need to do is get all external and internal stylesheets on the current page. Stylesheets are available as members of the global document.

document.styleSheetsThat returns an array-like object. We want to use array methods, so we’ll convert it to an array. Let’s also put this in a function that we’ll use throughout this post.

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets];When we invoke getCSSCustomPropIndex, we see an array of CSSStyleSheet objects, one for each external and internal stylesheet on the current page.

Step 2: Discard third-party stylesheets

If our script is running on https://example.com any stylesheet we want to inspect must also be on https://example.com. This is a security feature. From the MDN docs for CSSStyleSheet:

In some browsers, if a stylesheet is loaded from a different domain, accessing cssRules results in SecurityError.

That means that if the current page links to a stylesheet hosted on https://some-cdn.com, we can’t get custom properties — or any styles — from it. The approach we’re taking here only works for stylesheets hosted on the current domain.

CSSStyleSheet objects have an href property. Its value is the full URL to the stylesheet, like https://example.com/styles.css. Internal stylesheets have an href property, but the value will be null.

Let’s write a function that discards third-party stylesheets. We’ll do that by comparing the stylesheet’s href value to the current location.origin.

const isSameDomain = (styleSheet) => {

if (!styleSheet.href) {

return true;

}

return styleSheet.href.indexOf(window.location.origin) === 0;

};Now we use isSameDomain as a filter on document.styleSheets.

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets]

.filter(isSameDomain);With the third-party stylesheets discarded, we can inspect the contents of those remaining.

Step 3: Get all rules for the remaining stylesheets

Our goal for getCSSCustomPropIndex is to produce an array of arrays. To get there, we’ll use a combination of array methods to loop through, find values we want, and combine them. Let’s take a first step in that direction by producing an array containing every style rule.

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets]

.filter(isSameDomain)

.reduce((finalArr, sheet) => finalArr.concat(...sheet.cssRules), []);We use reduce and concat because we want to produce a flat array where every first-level element is what we’re interested in. In this snippet, we iterate over individual CSSStyleSheet objects. For each one of them, we need its cssRules. From the MDN docs:

The read-only CSSStyleSheet property cssRules returns a live CSSRuleList which provides a real-time, up-to-date list of every CSS rule which comprises the stylesheet. Each item in the list is a CSSRule defining a single rule.

Each CSS rule is the selector, braces, and property declarations. We use the spread operator ...sheet.cssRules to take every rule out of the cssRules object and place it in finalArr. When we log the output of getCSSCustomPropIndex, we get a single-level array of CSSRule objects.

This gives us all the CSS rules for all the stylesheets. We want to discard some of those, so let’s move on.

Step 4: Discard any rules that aren’t basic style rules

CSS rules come in different types. CSS specs define each of the types with a constant name and integer. The most common type of rule is the CSSStyleRule. Another type of rule is the CSSMediaRule. We use those to define media queries, like @media (min-width: 400px) {}. Other types include CSSSupportsRule, CSSFontFaceRule, and CSSKeyframesRule. See the Type constants section of the MDN docs for CSSRule for the full list.

We’re only interested in rules where we define custom properties and, for the purposes in this post, we’ll focus on CSSStyleRule. That does leave out the CSSMediaRule rule type where it’s valid to define custom properties. We could use an approach that’s similar to what we’re using to extract custom properties in this demo, but we’ll exclude this specific rule type to limit the scope of the demo.

To narrow our focus to style rules, we’ll write another array filter:

const isStyleRule = (rule) => rule.type === 1;Every CSSRule has a type property that returns the integer for that type constant. We use isStyleRule to filter sheet.cssRules.

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets]

.filter(isSameDomain)

.reduce((finalArr, sheet) => finalArr.concat(

[...sheet.cssRules].filter(isStyleRule)

), []);One thing to note is that we are wrapping ...sheet.cssRules in brackets so we can use the array method filter.

Our stylesheet only had CSSStyleRules so the demo results are the same as before. If our stylesheet had media queries or font-face declarations, isStyleRule would discard them.

Step 5: Get the name and value of all properties

Now that we have the rules we want, we can get the properties that make them up. CSSStyleRule objects have a style property that is a CSSStyleDeclaration object. It’s made up of standard CSS properties, like color, font-family, and border-radius, plus custom properties. Let’s add that to our getCSSCustomPropIndex function so that it looks at every rule, building an array of arrays along the way:

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets]

.filter(isSameDomain)

.reduce((finalArr, sheet) => finalArr.concat(

[...sheet.cssRules]

.filter(isStyleRule)

.reduce((propValArr, rule) => {

const props = []; /* TODO: more work needed here */

return [...propValArr, ...props];

}, [])

), []);If we invoke this now, we get an empty array. We have more work to do, but this lays the foundation. Because we want to end up with an array, we start with an empty array by using the accumulator, which is the second parameter of reduce. In the body of the reduce callback function, we have a placeholder variable, props, where we’ll gather the properties. The return statement combines the array from the previous iteration — the accumulator — with the current props array.

Right now, both are empty arrays. We need to use rule.style to populate props with an array for every property/value in the current rule:

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () => [...document.styleSheets]

.filter(isSameDomain)

.reduce((finalArr, sheet) => finalArr.concat(

[...sheet.cssRules]

.filter(isStyleRule)

.reduce((propValArr, rule) => {

const props = [...rule.style].map((propName) => [

propName.trim(),

rule.style.getPropertyValue(propName).trim()

]);

return [...propValArr, ...props];

}, [])

), []);rule.style is array-like, so we use the spread operator again to put each member of it into an array that we loop over with map. In the map callback, we return an array with two members. The first member is propName (which includes color, font-family, --color-accent, etc.). The second member is the value of each property. To get that, we use the getPropertyValue method of CSSStyleDeclaration. It takes a single parameter, the string name of the CSS property.

We use trim on both the name and value to make sure we don’t include any leading or trailing whitespace that sometimes gets left behind.

Now when we invoke getCSSCustomPropIndex, we get an array of arrays. Every child array contains a CSS property name and a value.

This is what we’re looking for! Well, almost. We’re getting every property in addition to custom properties. We need one more filter to remove those standard properties because all we want are the custom properties.

Step 6: Discard non-custom properties

To determine if a property is custom, we can look at the name. We know custom properties must start with two dashes (--). That’s unique in the CSS world, so we can use that to write a filter function:

([propName]) => propName.indexOf("--") === 0)Then we use it as a filter on the props array:

const getCSSCustomPropIndex = () =>

[...document.styleSheets].filter(isSameDomain).reduce(

(finalArr, sheet) =>

finalArr.concat(

[...sheet.cssRules].filter(isStyleRule).reduce((propValArr, rule) => {

const props = [...rule.style]

.map((propName) => [

propName.trim(),

rule.style.getPropertyValue(propName).trim()

])

.filter(([propName]) => propName.indexOf("--") === 0);

return [...propValArr, ...props];

}, [])

),

[]

);In the function signature, we have ([propName]). There, we’re using array destructuring to access the first member of every child array in props. From there, we do an indexOf check on the name of the property. If -- is not at the beginning of the prop name, then we don’t include it in the props array.

When we log the result, we have the exact output we’re looking for: An array of arrays for every custom property and its value with no other properties.

Looking more toward the future, creating the property/value map doesn’t have to require so much code. There’s an alternative in the CSS Typed Object Model Level 1 draft that uses CSSStyleRule.styleMap. The styleMap property is an array-like object of every property/value of a CSS rule. We don’t have it yet, but If we did, we could shorten our above code by removing the map:

// ...

const props = [...rule.styleMap.entries()].filter(/*same filter*/);

// ...At the time of this writing, Chrome and Edge have implementations of styleMap but no other major browsers do. Because styleMap is in a draft, there’s no guarantee that we’ll actually get it, and there’s no sense using it for this demo. Still, it’s fun to know it’s a future possibility!

We have the data structure we want. Now let’s use the data to display color swatches.

Step 7: Build HTML to display the color swatches

Getting the data into the exact shape we needed was the hard work. We need one more bit of JavaScript to render our beautiful color swatches. Instead of logging the output of getCSSCustomPropIndex, let’s store it in variable.

const cssCustomPropIndex = getCSSCustomPropIndex();Here’s the HTML we used to create our color swatch at the start of this post:

<ul class="colors"></ul>We’ll use innerHTML to populate that list with a list item for each color:

document.querySelector(".colors").innerHTML = cssCustomPropIndex.reduce(

(str, [prop, val]) => `${str}<li class="color">

<b class="color__swatch" style="--color: ${val}"></b>

<div class="color__details">

<input value="${prop}" readonly />

<input value="${val}" readonly />

</div>

</li>`,

"");We use reduce to iterate over the custom prop index and build a single HTML-looking string for innerHTML. But reduce isn’t the only way to do this. We could use a map and join or forEach. Any method of building the string will work here. This is just my preferred way to do it.

I want to highlight a couple specific bits of code. In the reduce callback signature, we’re using array destructuring again with [prop, val], this time to access both members of each child array. We then use the prop and val variables in the body of the function.

To show the example of each color, we use a b element with an inline style:

<b class="color__swatch" style="--color: ${val}">That means we end up with HTML that looks like:

<b class="color__swatch" style="--color: #00eb9b"></b>But how does that set a background color? In the full CSS we use the custom property --color as the value of background-color for each .color__swatch. Because external CSS rules inherit from inline styles, --color is the value we set on the b element.

.color__swatch {

background-color: var(--color);

/* other properties */

}We now have an HTML display of color swatches representing our CSS custom properties!

See the Pen CSS Custom Props to JavaScript - Complete by Tyler Gaw (@tylergaw) on CodePen.

This demo focuses on colors, but the technique isn’t limited to custom color props. There’s no reason we couldn’t expand this approach to generate other sections of a pattern library, like fonts, spacing, grid settings, etc. Anything that might be stored as a custom property can be displayed on a page automatically using this technique.

If you have thoughts about this post, email me@tylergaw.com or ping me on Bluesky.